But Why Don’t Medical Devices Need IEC 61508? A Look at the Latest Developments in IEC 60601-1 Edition 4

As the 4th edition of IEC 60601 heads to the committee draft version (CDV) 2nd stage in 2026, the question of functional safety or rather embedded system safety crops again. In late 2024 and 2025, a number of posts on social media discussed why the medical device sector does not need IEC 61508 – the standard for functional safety of electrical, electronic, and programmable electronic safety-related systems. With that, the inclusion of medical devices within the scope of IEC 61508 has been officially rejected at the end of 2024. And yes, while IEC 61508 may be excessive for the vast majority of medical devices, we do need a solution for the lack of embedded safety coverage in IEC 60601. In this blog we look at some of the challenges of developing safe embedded systems and how the medical device sector could improve its strategy.

Within the IEC 60601 community, there appears to be a reluctance to acknowledge the term functional safety. There is no doubt that the subject is complex and brings many challenges which, for the vast majority of medical device manufacturers, would be over the top. However, there are medical devices where functionality has safety-related implications, some of them critical. How does the industry support such customers?

The programmable medical electrical systems (PEMS) architecture section of the CDV 60601 edition 4 has not changed from edition 3 – the current version. A technical report, IEC 60601-4-9, has just completed its review phase (19 December 2025). Ultimately, however, IEC 60601-1 itself should support customers facing these challenges, rather than relying on a technical report. Section 14.8 of IEC 60601-1 edition 3 introduces a number of key terms, which we will look at in a bit more detail.

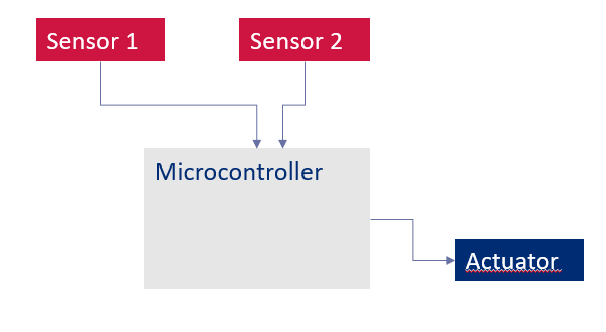

A common-cause failure occurs when two or more blocks in an architecture fail due to a single specific event or root cause.

In the example below, two redundant sensors are introduced to mitigate the risk of a single sensor failure. However, this raises further questions:

There are ways to improve the architecture, such as using diverse sensor types or implementing diverse software, partitioned inside the microcontroller.

Figure 1. Common-cause failure example

Cascading failures are not explicitly listed in section 14.8, but are indirectly referenced in section 4.7! A cascading failure occurs when a failure in one functional block results in failures in one or more subsequent blocks. This is of particular concern when the failing blocks are risk control mechanisms, as the benefit of having two risk control mechanisms is then lost. This phenomenon is often defined as the domino effect.

Diagnostic coverage (DC) is a widely used term across numerous safety standards and guidance documents, with slight variations in definition. Using the more generic definition from ISO 13849, diagnostic coverage is a measure of the effectiveness of diagnostics and may be determined as the ratio between the failure rate of detected dangerous failures and the failure rate of total dangerous failures.

Diagnostic coverage is very much a system-level attribute, as both hardware and software can contribute to the level achieved. Diagnostic coverage can be estimated in three different levels: low (60% ≤ DC < 90%), medium (90% ≤ DC < 99%), or high (99% ≤ DC). Alternatively, diagnostic coverage may be determined through calculation or by applying fault-injection tests, with the activity then becoming more scientific and evidence-based.

A typical example of diagnostic coverage levels within a system can be explained by considering the detection of failures in a power supply output.

| Element | Low DC (60%) | Medium DC (90%) | High DC (99%) |

| Power supply |

|

|

|

Table 1. DC examples for a power supply output

There are many system-level considerations when assessing diagnostic coverage. Sources such as IEC 61508 and ISO 13849 are helpful in defining DC for microcontrollers, bus systems, and analogue or digital I/O, to name but a few.

The main challenge associated with diagnostic coverage is relating it to a failure rate for the hardware components being analysed. This is where failure-in-time (FIT) rates from reliability sources come into play. The FIT rate of the hardware block or component is multiplied by the diagnostic coverage value, yielding a figure for the probability of detecting that given fault.

This approach takes failure modes and effects analysis (FMEA) to the next level, where both the occurrence probability and detectability columns become quantitative through the use of FIT and DC values.

Alastair Walker, Owner / Consultant

If these topics raise questions about your own products or development processes, feel free to get in touch via our contact form or email to discuss your specific situation.

Our team of consultants supports manufacturers with functional safety and IEC 60601 challenges on a daily basis.

Learn moreSystematic failures can occur when processes or procedures are lacking, often as a result of inadequate or incomplete requirements. Such failures may arise within an organisation’s own processes, or within the processes of manufacturers supplying components or functional blocks to imclude in a system.

Ways of addressing systematic failures include improving internal processes or, where the concern relates to the systematic failure of an external component or block, introducing additional risk control mechanisms to mitigate the associated risk.

Partitioning is a topic strongly linked to common-cause failures. By partitioning or segregating functionality, interference resulting from common-cause aspects can be minimised or eliminated. Interestingly enough, the forthcoming 2nd edition of IEC 62304 for health software has greatly improved its definition and handling of partitioning.

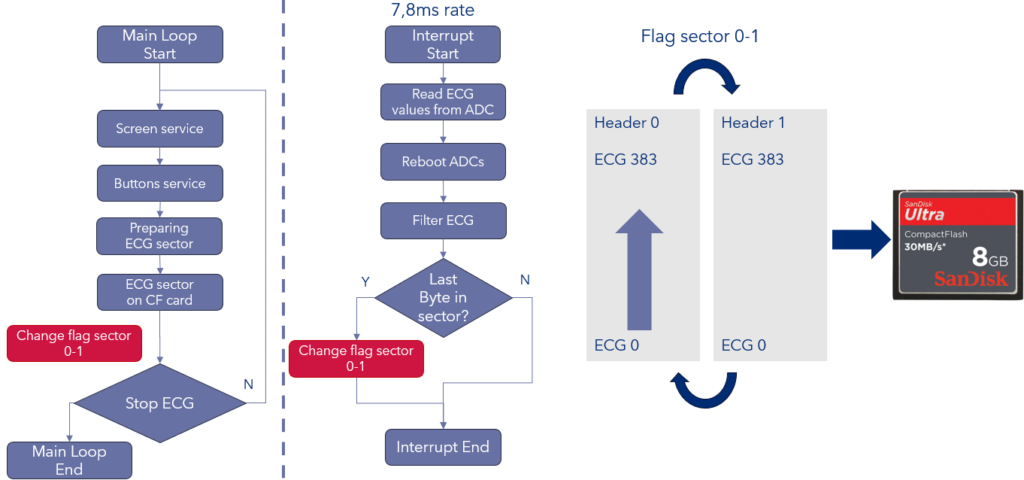

Partitioning refers to the avoidance of interference between different blocks in an architecture. In hardware, the use of separate power supplies or clocks are typical ways of reducing such concerns. In software, interference can be caused by sharing the same resources between two or more software modules. Even in a simple example of a 16-bit microcontroller used for ECG recording, interference can be introduced via e.g. the use of global variables in both mainline code and an interrupt. In such cases, partitioning is required, as both the mainline code and the interrupt may modify the RAM sector containing the ECG data.

Figure 4. Lack of partitioning and interference through a global variable

It is understandable that medical device manufacturers may be reluctant to introduce additional levels of complexity into their daily development activities. However, where patient safety is at stake, this complexity cannot always be avoided. The key question is when considerations such as those outlined above should be applied; ultimately, this must be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Starting with the product hazard analysis, it can be established which functional blocks present the greatest concern and the highest levels of risk, including the potential for death or serious injury. Where these blocks are embedded systems, or form part of embedded systems, the level of rigour described earlier should be applied.

IEC 60601-1 edition 3, and the work on edition 4 to date, define a strategy for programmable medical electrical systems (PEMS) based on risk decisions. However, guidance on how to apply this strategy when the risk is high remains the missing link.

Functional safety, and safety related to embedded systems, are challenging technical areas. However, for medical devices – as with products in many other industries – they play a key role in minimizing the risks of embedded products. As IEC 60601-1 edition 4 continues to develop, we will see where things go. At present, however, the medical device industry appears to trail other sectors in this area.

Pragmatic approaches can be used, with the first challenge being a clear understanding of the underlying problems. On the other side of the coin, the desire not to be constrained by complex standards such as IEC 61508 is also an understandable position. Ultimately, progress in this area will depend on open discussion, shared experience, and a willingness to learn from approaches adopted in other industries.

By Alastair Walker, Owner / Consultant

If you would like to explore these topics further – through targeted consultancy or practical training – our team would be happy to support you.

Contact us at info@lorit-consultancy.com or via a contact form to start a conversation about your needs.